On Voicings for Mixed Barbershop Choruses

I am returning to this theme as a lot of people are grappling with the challenges of making a genre developed for and within single-sex ensembles work with mixed groups. Having interacted with a number of different ensembles in various capacities in recent times, I wanted to collate what I’ve learned from them about the difficulties they’ve faced and the solutions they have found.

First, though, it is worth thinking through why mixed barbershop can prove tricky, before looking at the consequences for lived experience, and what we can do about it. This may turn into more than one post; it has the feel of a question that expands as you think about it!

So, let’s start with the human voice. Your range is delimited at the bottom end by the size of your larynx: the longer your vocal folds are, the lower your range can extend. The top end can be extended with practice, and all healthy adults can reasonably expect to get it up to about 3 octaves above their lowest note (though it takes a certain level of dedicated practice to keep the full range). Most people who sing regularly have a useable range of about 2-2 ½ octaves, assuming that we avoid using the extremes for performance purposes as we tend to lose quality there.

The size of your larynx, like your height and your shoe size, is determined by a combination of genetics and developmental experience (childhood nutrition etc) – that is, we can’t control it. And one of the development things we can’t control is the effect of puberty on the voice: all people experience some change, but those with male bodies have a much more dramatic change. As well as larger skeletons and increased muscle mass, young men also experience much greater laryngeal growth than young women.

This is a round-the-houses way of saying that, on average, men have lower voices than women. Which we knew, but it’s worth thinking through the mechanics of this: it’s not just a musical convention, it’s a feature of biology. Not all men have lower voices than all women, of course: there is considerable variation within each sex, and considerable overlap between them. (Indeed, there is rather more overlap than much classical SATB writing might lead us to believe, and without it we wouldn’t even be considering mixed barbershop a viable possibility.)

Let us assume a normal distribution bell curve for vocal ranges within each sex.

Normal distribution

Normal distribution

I’ve not actually seen concrete research documenting this, but it is clear through experience that a few people have unusually high or low voices, rather more have quite high/low voices, and a lot are kind of middling, perhaps tending a bit on the low side or a bit on the high side. So, whilst it is possible that the actual curve for vocal ranges might skew a bit one way or the other, it's going to be close enough to normal distribution for the classic curve to be useful for this analysis.

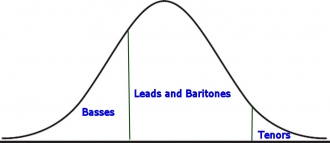

And traditional barbershop voicing maps well onto this, with one high part, one low part, and two middling parts occupying the middle ground. We tend to skew a bit to the high side in how we divvy people up into parts, as for acoustical reasons we want more voices at the bottom end than at the top, and as the bass is usually the most rangy part, it’s suitable for the reasonably low as well as the unusually low voices.

Bell curve with barbershop voicings

Bell curve with barbershop voicings

And this works within the bell curve for each sex, with the centre of gravity of each about a 5th apart. One of the things that’s great about women’s barbershop, incidentally, is the way it uses the lower voices well. A lot of female basses spent their school years feeling uncomfortable because the music they were expected to sing sat too high for them. Fortunately, classical choirs are becoming more accommodating to female tenors now, so lower-voiced women are better served than hitherto.

(Whilst male and female groups both have a similar-shaped bell curve of available ranges, the absolute ranges of the two types of ensemble, and thus how one best writes for them, are not the same, as discussed in a couple of posts last year. There are acoustic as well as vocal factors in the difference between higher and lower voiced barbershop, but for today’s argument, the key point is that both forms of single-sex ensemble are optimised for the distribution of vocal ranges in their constituent populations.)

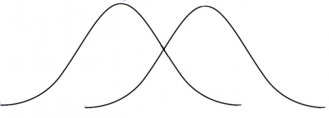

Now let’s look at what happens when you combine these two bell curves into a mixed ensemble. If you are a classical group, there’s a clear split between the SA world of the women and TB world of the men (though as noted above, vocal outliers from each curve are these days – helpfully - more likely to be classified by actual vocal range than by sex).

Combining bell curves for female and male voices

Combining bell curves for female and male voices

For barbershop, though, if you try and pitch things for a middle-ground between the two groups, the shape of the graph works against you. You’ll not be short of basses, as those who were middling in the male-only curve now occupy that part of the texture. Meanwhile, you’ll be over-supplied with tenors as a lot of the middling-high voices from women’s barbershop who would sing lead or baritone move up to the top part. Meanwhile, you get a dip in the population in the middle bit where lead and baritone parts live, leaving both parts either underpopulated, or filled with people singing outside their best range.

I’ve presented this as a theoretical exercise, but it describes the real-life situations of various choruses I have encountered. I have come across groups which are bass- and tenor-heavy because singers people migrated to the parts that best fit their voices, and also groups where many of those singing lead and baritone were singing out of their best range. (Usually this involves pitching things on the low side so that the guys don’t overstrain but the women are growling; as with the Harmony Brigade scene, it is apparently preferable to inconvenience women than men.)

When groups pitch things up enough that the female singers aren’t quite so out of their best range, you then find that the lower basses amongst the men no longer feel that they have a home. This is both an identity problem, and a musical waste not to use that lovely low resonance when you have it. The same can be said of the higher female voices; whilst one can criticise the classical world for pushing sopranos unreasonably high for much of the time, it would be a pity never to use the top end where the voices can fly free.

That’s probably enough for one helping. To be continued…

...found this helpful?

I provide this content free of charge, because I like to be helpful. If you have found it useful, you may wish to make a donation to the causes I support to say thank you.

Archive by date

- 2024 (19 posts)

- 2023 (51 posts)

- 2022 (51 posts)

- 2021 (58 posts)

- 2020 (80 posts)

- 2019 (63 posts)

- 2018 (76 posts)

- 2017 (84 posts)

- 2016 (85 posts)

- 2015 (88 posts)

- 2014 (92 posts)

- 2013 (97 posts)

- 2012 (127 posts)

- 2011 (120 posts)

- 2010 (117 posts)

- 2009 (154 posts)

- 2008 (10 posts)