Add a comment

Right Sex, Right Instrument

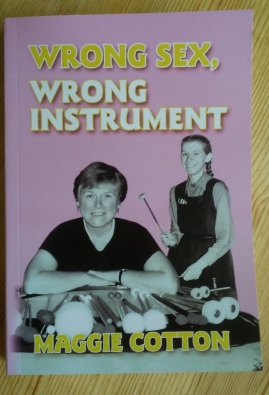

‹-- PreviousNext --› Last week I attended a talk, hosted by the Balsall Heath Local History Society, by Maggie Cotton about her career as the UK’s first female percussionist in a professional orchestra. It bore the same title as her autobiography, ‘Wrong Sex, Wrong Instrument,’ which was the reason she was given, age 19, for being refused a grant to study at the Royal Academy of Music.

Last week I attended a talk, hosted by the Balsall Heath Local History Society, by Maggie Cotton about her career as the UK’s first female percussionist in a professional orchestra. It bore the same title as her autobiography, ‘Wrong Sex, Wrong Instrument,’ which was the reason she was given, age 19, for being refused a grant to study at the Royal Academy of Music.

The talk was, as you can imagine, fascinating in many dimensions. My main focus in blogging about it is going to be the dimension of music and gender – unsurprisingly, given my interests as a musicologist all these years. But one of the striking things about the talk, notwithstanding its title, was how little gender obtruded into the stories. Most of the time it was a collection of tales from a percussionist, about her travels, about the instruments, about the conductors, composers and fellow players she had worked with.

Which itself is a key point. There is in fact nothing about being female that prevents you from being a percussionist. The tales of obstructionism from people who thought otherwise were almost exclusively from her youth and early career, and their role in the narrative was as distractions and killjoys that Maggie just needed to get past to focus on the main business of really, really enjoying playing percussion.

Three things struck me about the obstacles Maggie encountered. The first was that they were a good deal more blatant that those encountered by my generation. By the time I was 19, it was no longer normal to say, ‘girls don’t do that’. (There was that ‘how do you think the choir will react to being conducted by a woman?’ incident when I was 20, but it was not to my face, and the perpetrator of that question was roundly scolded by the person he asked.) I found the bluntness of some of the people who tried to stop Maggie quite breathtaking, but the way she recounted the stories, it was that bluntness that gave her Yorkshire-bred bloody-mindedness something to push against.

The second point to note was that the obstacles weren’t universal. She received a good deal of support and encouragement, as well as the outright opposition, both from music educators and within her family. We tend to stereotype past eras as inherently more sexist than today – not least because of the overtness of the constraints – but it was clear that the 1950s produced a good many folk who did not harbour unduly limiting attitudes as well as those who did. Her uncles might have thought she should get married forthwith, but her father pushed her to take up her place at the Academy despite her mother’s death shortly before she was due to go.

The third thing I noticed was that the obstacles were both internal and external. It took the direct intervention by a National Youth Orchestra percussion tutor to counter her assumption that she couldn’t got to college to study percussion because that’s not what girls did. Once she was over that barrier, she was all set to transcend the intermittent external difficulties.

For the first 10 years of Maggie’s time with the CBSO, she remained the only woman in the orchestra. It was not clear from the talk exactly when or how that changed, but she did talk about how Simon Rattle was open about liking to have women in the orchestra, as the culture became ‘less like a football changing room’.

You can see the cultural distance travelled between 1960 when Adrian Boult was Principal conductor and 1980 when Rattle was appointed in a quip of Boult’s from her early career. Can you imagine Rattle saying to a woman playing the cymbals that he wanted her to be known ‘as the woman with the largest pair in the midlands’?

That is the kind of anecdote that gets cosily told and retold about the wit and raffishness of the conductors of yesteryear, and it feels safe because it is distant. (Indeed, we know the story travelled as it was retold back to Maggie some years later when she was playing in Sydney.) But when it’s told by the person to whom it was addressed, you can’t help wonder how you’d feel if you were the only woman in the room and the person in charge made a joke that invited all the other men to think about your tits. It doesn’t feel very cosy then. Maggie tells the story without rancour, but it’s also clear that she much prefers a world in which she is simply one of the team.

The picture above is her book, which I bought at the event and have not yet read. But I’m going to recommend it in anticipation, as I already know she is an excellent story-teller.